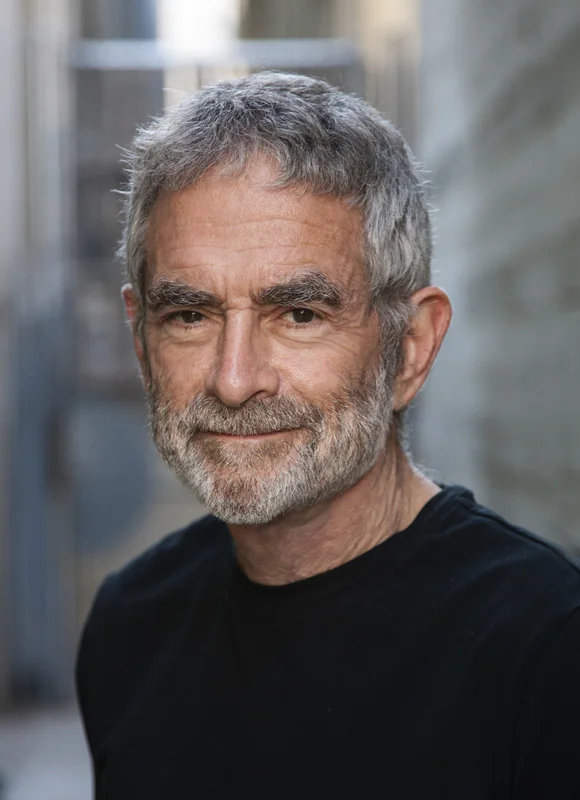

INTERVIEW WITH ED FREEMAN

Ed Freeman is a true creative. His many talents reach across the visual,audible and cerebral worlds. In his early career, Ed worked in the music industry; he performed as a folk guitarist and classical lutenist, worked as a road manager for the Beatles on their last tour, played guitar on many pop recordings, wrote orchestral arrangements for artists such as Cher and Carly Simon, produced and arranged over two dozen albums – including Don McLean’s American Pie. Now, Ed creates fine art and commercial photographs. His work has been extensively published and his architectural series, Desert Realty and Urban Realty, have been the subject of touring museum shows.

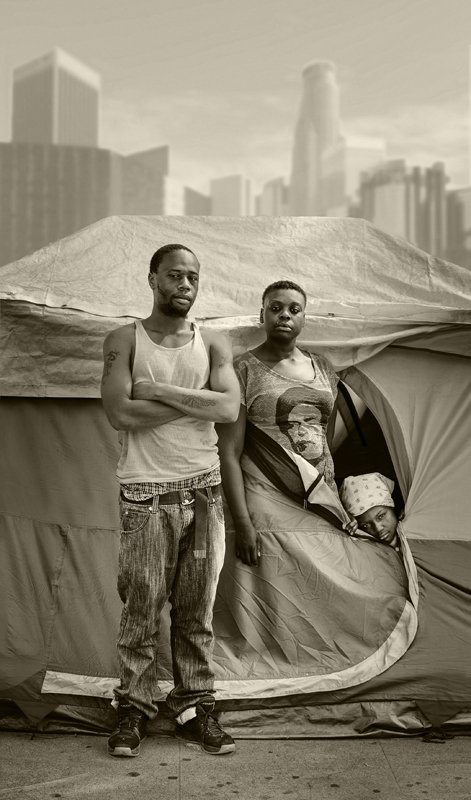

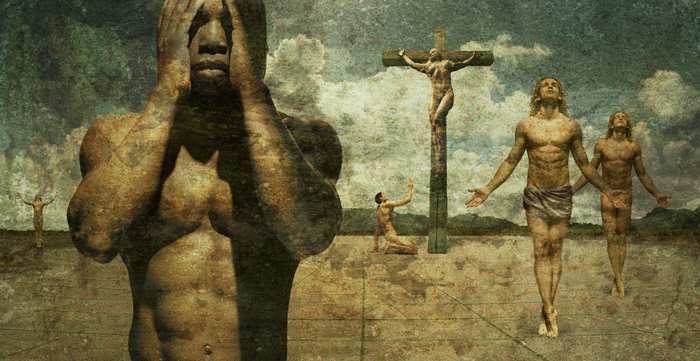

Ed’s photography captures an elusive ethereal beauty we can all appreciate and revere. In contrast, his Homeless series captures reality at its bleakest, the visualization of communal abandonment – humanity averting its gaze from those less fortunate of neighbors. For Ed – photography is not only about the subject but about the human behind the lens.

I’ve been taking pictures all my life, but I didn’t turn professional full-time until I was almost fifty, after a long career as a musician and record producer. When I got out of college, I had to choose between making pictures and making music. Initially I chose making music, because I thought it was more “spiritual.” That was pretty naive. “More spiritual” was just a euphemism for “more drugs.” The first photo I ever sold was a football picture I took in junior high school. I sold it to the Boston Globe for five dollars. When I was producing records, I shot a few album covers here and there. Now I work at photography obsessively, all day, every day. Some people think that means I have a terrific work ethic, but I don’t. I’m just doing what I love to do.

I never studied photography, and sometimes I regret it, because I could have saved myself a lot of time that I spent reinventing the wheel. Technique is just technique – the faster you get it under your belt, the better. On the other hand, I’m glad I didn’t get influenced artistically by any teacher. Most of the photography teachers I’ve met shouldn’t be teaching aesthetics, or creativity, or taste, or art, or anything more esoteric than focal lengths and f-stops. So what I’d recommend to anyone starting out is yes, absolutely, get yourself a good grounding in technique; go to school. But take everything your teachers tell you with a grain of salt. I promise you, their way is not the only way. And don’t just look at what your friends are shooting; spend some time in the library looking at books of photographs from the great masters – why not learn from the best?

HOMELESS

What separates the rest of us from people living on the streets, people living from hand to mouth, is a lot less significant than what unites us. We’re all imperfect, struggling humans. Maybe homeless people have less coping skills than people living in Park Avenue condos, but that’s it. We all want meaning in our lives; we all want to experience happiness and to know that our time on Earth has made a difference. That’s what I want to photograph.

When I started shooting professionally, I did about a thousand actors’ headshot sessions, which almost turned me off forever shooting portraits. I started by shooting headshots because that was the simplest thing I could think of doing. Headshots are about making people look like what they want to look like; portraiture, for me at least, is about making people look like who they really are. Huge difference! I’ve always been interested in portraiture; when I was 15 years old I apprenticed in a portrait studio in Cambridge and I’ve been shooting portraits ever since. I love portraiture. But I’d rather starve than go back to shooting headshots.

I had never assisted and I had no idea that photographers were supposed to specialize. So I did everything – portraiture, architecture, tabletop, food, lifestyle, travel; I shot for Warner Bros., Colombia Records, Sony, Miller Beer, Trader Joe’s – lots of commercial accounts. Then I hooked up with Getty Images and sent them some of my vacation snapshots – and to my surprise, they sold. The more I sent them, the more they sold. Eventually, I stopped doing everything else and concentrated on shooting travel stock – which is a lot more fun than photographing hamburgers and machine parts. Just about the time I gave up doing commercial work entirely, the stock photography market crashed and burned – suddenly, I was not making any money. Probably the dumbest thing I could have done at that time would have been to go into making fine art full time, but that’s exactly what I did. And after a bit of a rocky start, amazingly, it worked. That’s how I make my living now – shooting fine art and selling limited edition prints. I still do an occasional magazine or CD cover, and if I had a photo rep I’d probably do more because it’s fun – but I’m also very content doing what I do now.

I live and work in Los Angeles – maybe not the intellectual capital of the world, but very possibly the creative capital, for photographers at least – and for outdoor shooters like me, the weather is close to ideal. I usually just call myself a photographer. “Fine art” photographer – sounds so snooty. So I sort of bury it at the end of a sentence. When people ask me, “What kind of photography?” – I say, “Oh, lots of stuff. Landscapes, travel, underwater, portraits, architecture, advertising, fine art…” And if I have to squeeze my pitch into one sentence, I say, “I do computer-enhanced photography that doesn’t look computer-enhanced.” That’s my elevator pitch. But I don’t spend a lot of time in elevators these days.

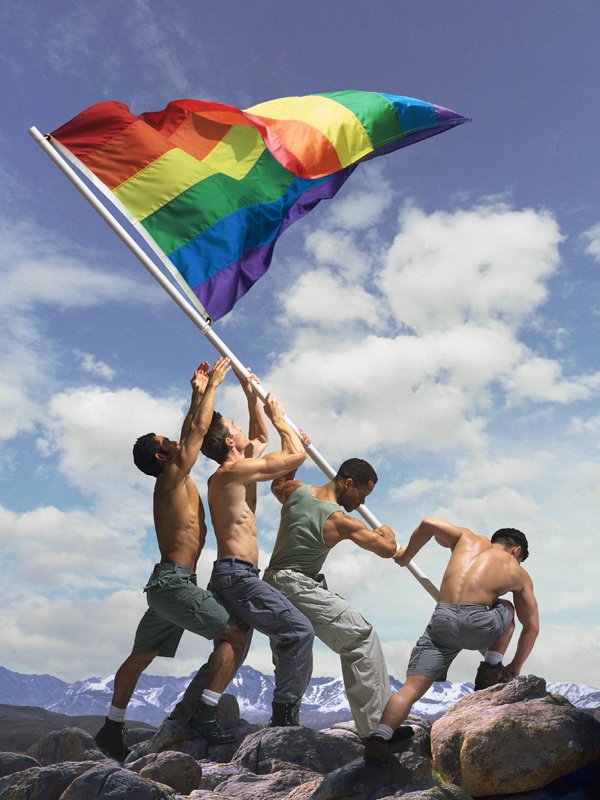

The Gay Pride picture was fun – I got about five thousand hate mails, including death threats, and I got outed on Fox News and any number of newspapers and blogs. I just take it as part of a long, evolving process that our society has to undergo – realizing that we humans are all the same and we all deserve an equal chance at having a good life.

When I’m prepping for a shoot, I make sure all the technical stuff is in place – equipment, lighting, props, etc. Some of my shoots, especially the underwater ones (I can’t even swim, let alone dive!), require days of preparation; I’ve had as many as twenty models, plus three or four assistants on them. So I do a lot of advance work. But I rarely preconceive specific pictures. I just set up situations, and then, whatever happens, happens. I shoot with a Nikon® D800E and four or five lenses. I have some ancient Balcar flash equipment that still works when it’s in a good mood. I used to be an equipment junkie – I still have a 4×5 and a Widelux gathering dust in the basement – but as time goes on I’ve pared down a lot. And these days I spend a lot more time in front of a Mac® computer than I do shooting.

I’m pretty easy to work with, but I expect a high degree of professionalism from my assistants and models. I have a great first assistant and on big shoots I use a lot of interns. Anybody who doesn’t measure up I politely suggest that they go pick up sandwiches – at some very far away sandwich shop. I get criticized all the time! Some people absolutely despise what I do, including some very close friends! I listen to them, I respect their opinions. If anything they say rings true for me, I take it in. There have been times when constructive, or even destructive, criticism has changed what I do. But most of the time I see criticism as being less about what I’m doing and more about the person doing the criticizing. And most of the time, criticism doesn’t bother me one bit. I just find it interesting.

My favorite image is almost always my most recent one. Thank God. I’d hate it if my favorite was one I’d taken ten years ago – I’d always be thinking, “Oh, I was good then, but I’m not that good anymore…” That would be unbearable. Success is wherever I’m at now, plus 50%. I never think of myself as successful; I’m always “on my way there.” On the other hand, if all my bills are paid and I can still afford an occasional meal in a nice restaurant, I feel great! Maybe that’s success. There are so many amazing, creative photographers out there. If I could change anything, I’d make all of them a whole lot worse than they are, so by comparison, I’d look better! Just kidding, guys, don’t get all weirded out…

I don’t believe in inspiration; I believe in hard work. I had a music composition teacher who used to say, “a synonym for creativity is 9:00 a.m.” In other words, your reverence for inspiration is just self-indulgence. Sit your ass down at the piano – or the computer – and get to work, whether you feel like it or not. Don’t worry about “inspiration.” It will come. I’m very fortunate in that I almost never experience a creative “dry spell” and if I do then it only lasts for a few hours. That usually means that it’s time to stop making pictures and pay bills instead, or do the laundry… I still play the piano and dream about writing the Great American Symphony and the Great American Novel, neither of which will ever happen, but it’s always fun to fantasize. I do have a great novel in me. So far I’ve written the first and last sentence. That’s it, and I’ve been working on it for twenty years.

I find myself saying this over and over again: photography has surprisingly little to do with what your subject matter is and a whole lot to do with who you are as a human being. Ten people can use the same equipment to take the same picture and come out with vastly different results. If you really want to evolve as a photographer, do something else: learn to play the guitar, read poetry, listen to Peruvian folk music, talk to old people, go to museums, hang out with babies, meditate, pray, study. Whatever evolves you as a human being will evolve you as a photographer.

I thoroughly expect to be forgotten in a trillion years, and anything less than that is just short-term. But for sure I hope I make images that will have some resonance, not just today, but in the future. My pictures aren’t responses to day-to-day issues; I’m too old to be involved in that kind of art. I’m more interested in questions that don’t change from one moment to the next – What is the nature of human nature? Is there a God? What makes something beautiful? What am I called upon to do?

These buildings are in small towns spread out across all of the western United States. Real estate is cheap in these towns. When a building has outlived its useful life, it’s often not cost-effective to tear it down. A lot easier to just move on down the road and build a new one.

I love old, dilapidated buildings. Sometimes they seem sad, or wistful, or poignant to me; other times, I think they’re hilarious. Some of them seem to make political statements about our threatened American dream; others are souvenirs of a life and a way of being long gone.